by Oriol Domingo

This is the first post of a new post series where we will review the thesis presented by our students during the academic year 2020/21. Our goal is to share the research done by our students in their thesis, in a more accessible format, reaching a broader audience.

The complete thesis on which this post is based can be found here.

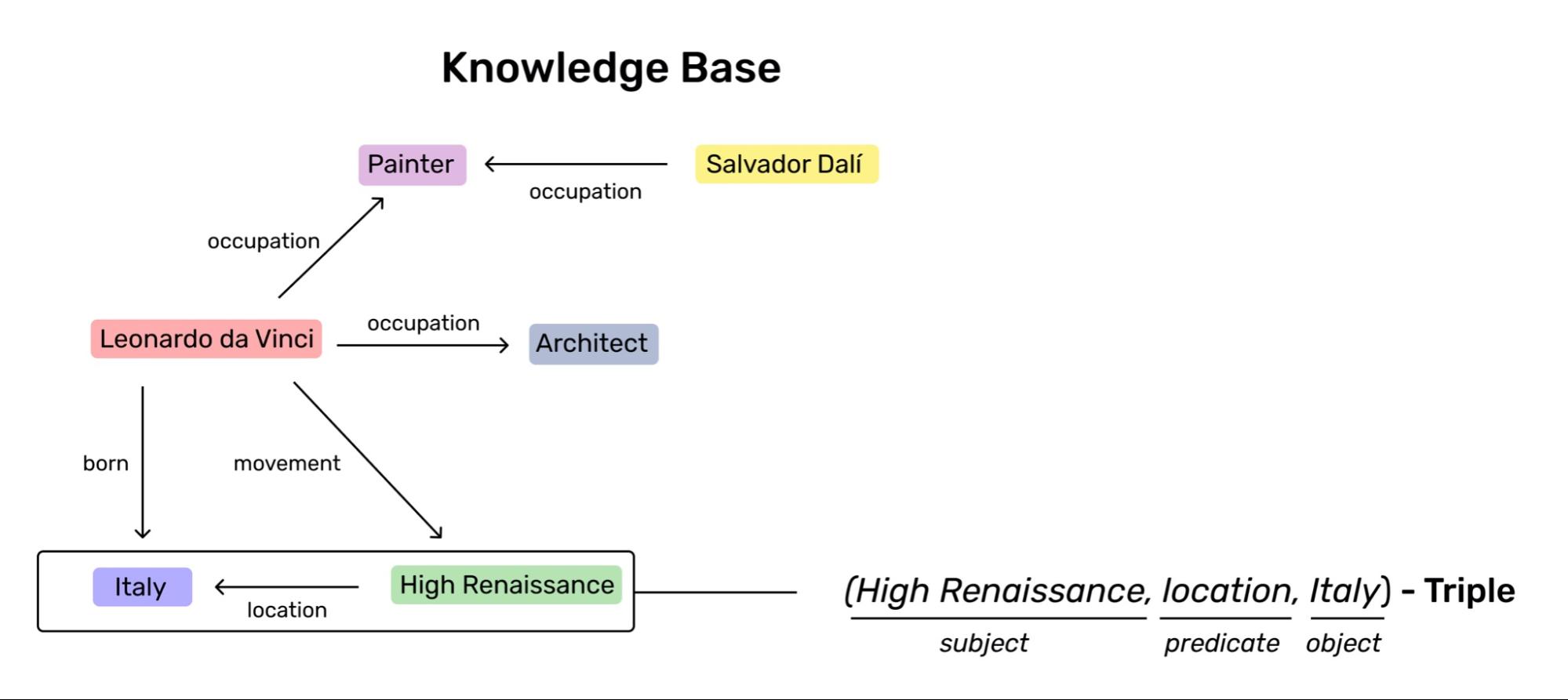

Nowadays, the Artificial Intelligence industry has leveraged the power of computation along deep learning models to build cutting-edge applications. Some of these applications, such as personal assistants or chat-bots, heavily rely on Knowledge Bases. These databases aim to represent facts about specific domains and ways of reasoning about those facts to draw new conclusions or highlight inconsistencies.

For example, imagine you are a tourist visiting Barcelona, and want to visit some well-known monuments in the city. You may probably wonder: Which monuments should I visit in Barcelona?, but the answer is simple, ask Siri.

Basically, Siri, or any other voice assistant, is able to answer this question thanks to the knowledge that is integrated in its engine, but such knowledge needs to be extracted, as well as updated. Furthermore, voice assistants should exhibit human capabilities in terms of voice and language. Focusing on the latter, the system needs to automatically generate natural language sentences embedding the corresponding knowledge to answer the user-queries.

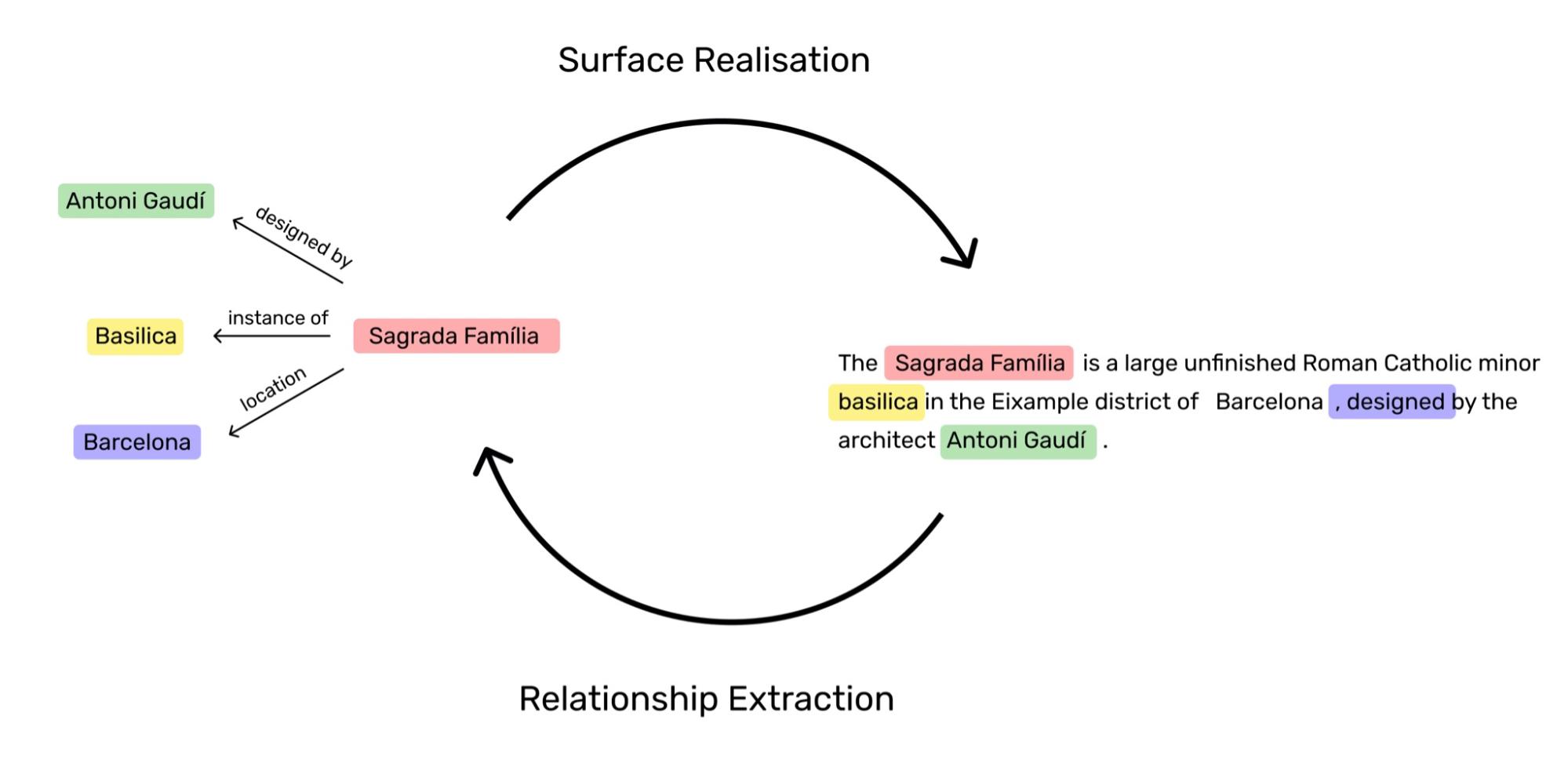

As it can be seen in the figure below, these facts are represented by three elements (hereinafter triples) : a subject establishing a relationship with an object through a predicate <subject, predicate, object>. Commonly, both, the subject and object, are referred as entities, which can be mentioned at several triples in any position, regardless of the predicate.

However, tech companies need to solve the following issues in order to build and offer accurate applications or services on top of these databases:

- Continuous Information Extraction to keep the knowledge base updated according to the (world) situation (Ji & Grishman, 2011).

- Building a data representation on top of the knowledge level that is human- friendly, i.e. that is comprehensible (Gardent et al., 2017).

In this post, we will focus on techniques that have been implemented in the recent literature to cope with both issues on textual data, and how we can implement a cycle training framework for lifelong learning.

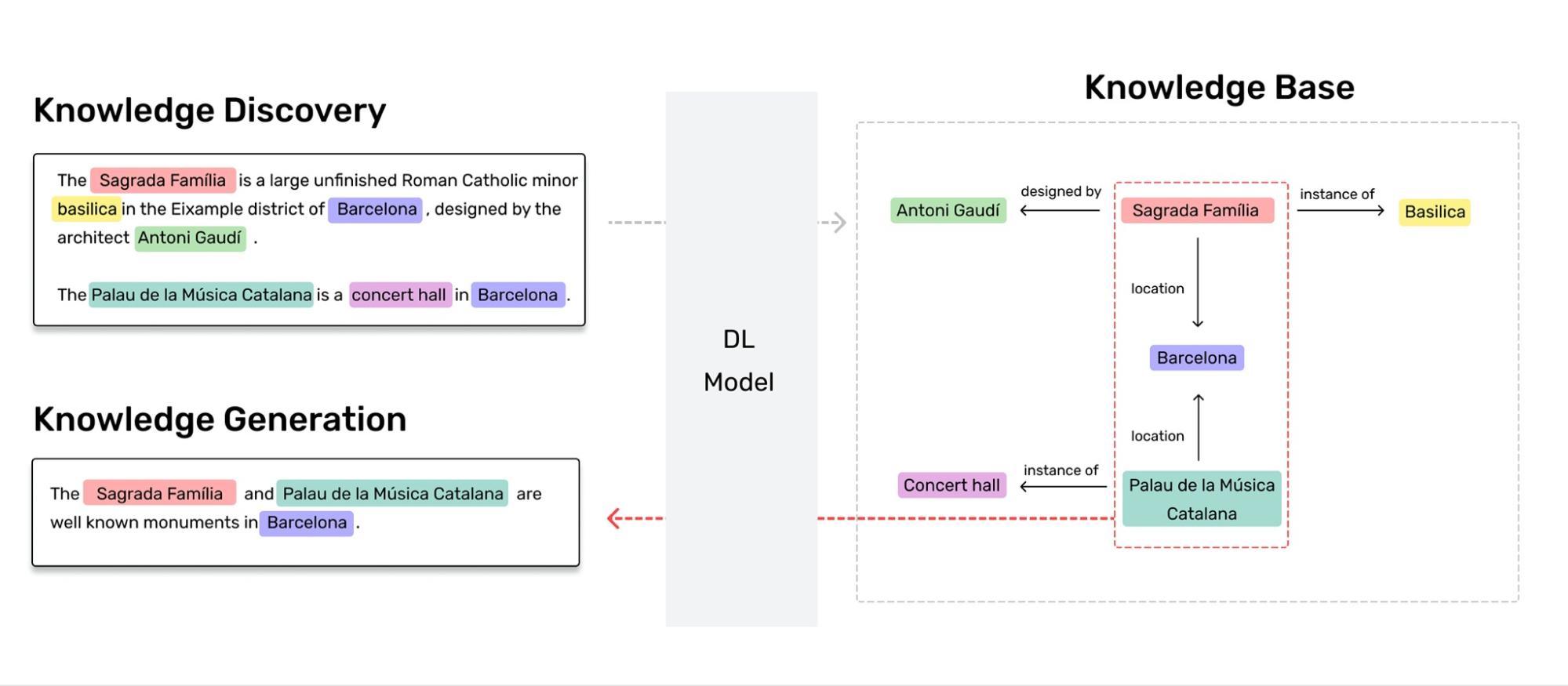

Thus far, we can understand Knowledge Discovery as the procedure to uncover new hidden facts given a source, before feeding them into the database. Besides, we also conceive Knowledge Generation as the method to produce text, which embeds the whole information of the retrieved knowledge (triples), given a query. An overview of these procedures, with a deep learning model, is depicted in the next figure.

For the advanced reader or domain expert, these procedures or methods have been tackled under Relationship Extraction and Surface Realisation tasks during the last decades (Belz et al., 2011; Leng & Jiang, 2016). At the beginning of this century, models heavily relied on statistical methods (Cohen & Hersh, 2005), however, during the last years end-to-end deep learning approaches (Agarwal et al., 2020) (Liu et al., 2020) have surpassed those early statistical models reaching state-of-the-art results, following the tendency in other domains.

Deep learning models significantly improve at the expenses of data. However, there is always an implicit trade-off between generalisation and memorisation of the training data (Feldman & Zhang., 2020). Most of the unsupervised techniques that are applied to deep learning models are designed to overcome such an issue, but also the data scarcity one (Artetxe et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020).

Multi-task learning is a learning environment in which several tasks are simultaneously learned by a single model. Such an approach offers advantages like improved data efficiency, reduced overfitting through shared representations, and fast learning by leveraging auxiliary information (Crawshaw, 2020).

Now, we are going to discuss how to tackle previous tasks using the combination of both, semi-supervised and multi-task learning.

We can formulate a Knowledge Base as a labeled directed graph ( ) over the triples in the database. Monolingual corpus, particularly text, can be easily formalised as a set of sentences, which are sequences of words (

). Then, given a data set of supervised examples (

), we can train a single model to do both, Relationship Extraction and Surface Realisation from

.

Ideally, this model ( ) is optimised over

by means of a maximum log-likelihood estimation:

At this point, we formulated a multi-task set-up, but this is an optional step since one can implement the following cycle training regime with two different models as well, one for each task.

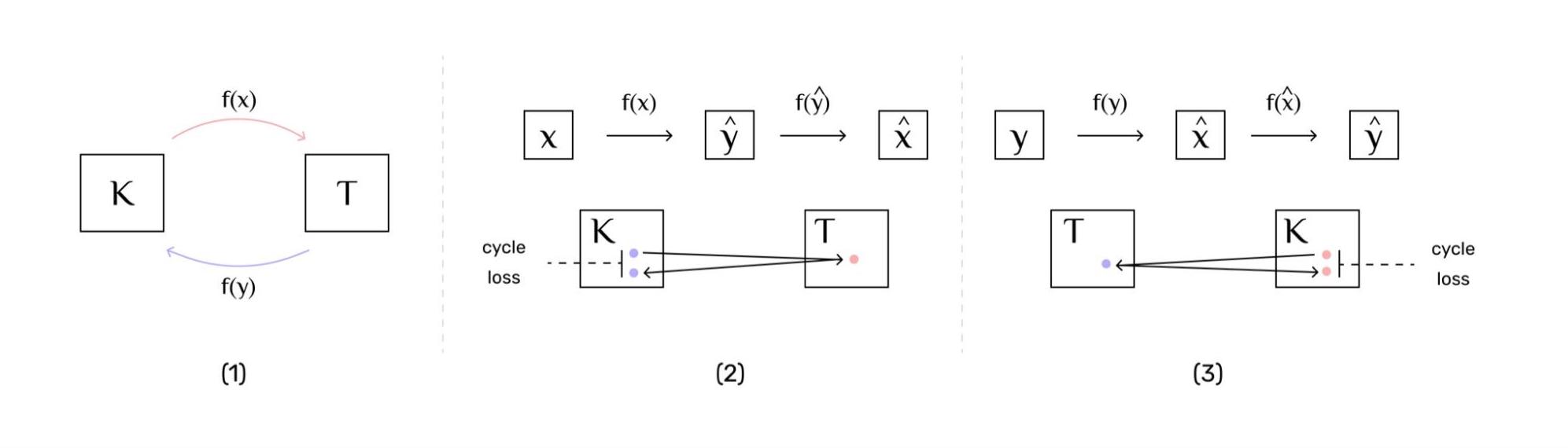

Cycle training was originally suggested as an image-to-image translation, rather than text-to-text (our current approach), a problem where the goal is to learn a mapping between an input image and an output image (Zhu et al., 2017). The main constraint for using cycle training is that there must exist two complementary tasks that guarantee that the input of one task is the output of the other task, and vice-versa.

If the previous constraint holds (existence of complementary tasks), which is our case, then, it is possible to build a bijective mapping function that given a variable satisfies

, where

is the inverse function of

. In our case, both functions represent the same model, hence, it holds that

, which is an involutory function.

This mathematical framework allows training without or with few parallel data. The main idea is that the model can learn from unlabeled data: unlabeled triples

and unlabeled text

; using its own predictions over these non-parallel data. Finally, the optimisation pass for both cycle losses can be back-propagated together on each batch.

To summarise, the model translates the triples (text) into text (triples), and this synthetic text (triples) is used as an input to predict the real triples (text), as it happens with Back Translation. Exemplified in the figure below with steps (2) and (3). However, the cycle framework has the advantage to iteratively improve the approach to both tasks, resulting in a lifelong learning loop.

To evaluate and assess the performance of this framework, one needs to collect parallel data for the early fine-tune phase of the training regime, as well as triples and monolingual text for the unsupervised phase.

One of the most common parallel datasets is the WebNLG corpus, a benchmark on which to evaluate and compare Knowledge Generation & Knowledge Discovery systems. Its latest release dates back to 2020, which includes Russian language and data for semantic parsing, due to the 2020 WebNLG+ challenge (Ferreira et al. 2020).

Collecting unsupervised samples, triples and text that do not have any cross reference, i.e. they are independent, can be done using Wikidata and Wikipedia respectively.

The T5 architecture (Raffel et al., 2020) is a good choice for the single model, because it easily integrates in a multi-task environment thanks to its text-to-text problem approaching framework. Such a model can be implemented using the Hugging Face library in Python, depending on the resources and capacity of your machine, you can leverage your power with different models’ depth. But the model architecture does not need to be this one, otherwise, the developer can choose any other suitable for Natural Language tasks.

Using a pre-trained T5-Base model, one can obtain the following results in Relationship Extraction:

-

Input:

Leonardo da Vinci was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance. -

Output:

<s> Leonardo da Vinci <p> occupation <o> polymath <s> Leonardo da Vinci <p> time period <o> High Renaissance

This is a pretty good parsing from unseen input, however, the model fails to retrieve the nationality of Leonardo da Vinci, which can be inferred by the word “Italian”.

The following example is regarding the Surface Realisation task:

-

Input:

<s> Brexpiprazole <p> instance of <o> Medication <s> Brexpiprazole <p> physically interacts with <o> Dopamine receptor D2 -

Output:

Relative to brexpiprazole, it physically interacts with Dopamine receptor D2.

Although the generated text provides some information embedded in the original triples, sometimes models tend to forget about some of them, and hence, they suffer from data coverage, which leads also to a poor text structure.

This post’s main goal has been to train an end-to-end multitask semi-supervised model for Knowledge Generation and Knowledge Discovery, so it can be used in industrial applications using Knowledge Bases, or in any particular project. During this development, we analysed and observed interesting properties regarding our approach, which can be summarised as follows:

- Cycle training can be adapted to the use-case of a single model, i.e. in a multi-task environment for natural language tasks.

- This lifelong learning system gives the advantage to easily train the model on new unlabeled data, even from a different domain.

- Our unlabeled data notably exceeds the labeled one, in particular, this is beneficial for minor languages or tasks under-represented, such as Basque or Relationship Extraction respectively.

I want to specially thank Marta R. Costa-jussà for her supervision and comments during the development of this project, and also, Carlos Escolano for his technical feedback. This would not have been possible without the help and support of the UPC’s Machine Translation group.

-

Agarwal, O., Kale, M., Ge, H., Shakeri, S., & Al-Rfou, R. (2020). Machine translation aided bilingual data-to-text generation and semantic parsing. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Natural Language Generation from the Semantic Web (WebNLG+) (pp. 125-130).

-

Artetxe, M., Labaka, G., Agirre, E., & Cho, K. (2018a). Unsupervised neural machine translation. In 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018.

-

Belz, A., White, M., Espinosa, D., Kow, E., Hogan, D., & Stent, A. (2011, September). The first surface realisation shared task: Overview and evaluation results. In Proceedings of the 13th European workshop on natural language generation (pp. 217-226).

-

Cohen, A. M., & Hersh, W. R. (2005). A survey of current work in biomedical text mining. Briefings in bioinformatics, 6(1), 57-71.

-

Crawshaw, M. (2020). Multi-task learning with deep neural networks: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.09796.

-

Feldman, V., & Zhang, C. (2020). What Neural Networks Memorize and Why: Discovering the Long Tail via Influence Estimation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 2881–2891). Curran Associates, Inc.

-

Ferreira, T., Gardent, C., Ilinykh, N., van der Lee, C., Mille, S., Moussallem, D., & Shimorina, A. (2020, December). The 2020 bilingual, bi-directional webnlg+ shared task overview and evaluation results (webnlg+ 2020). In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Natural Language Generation from the Semantic Web (WebNLG+).

-

Gardent, C., Shimorina, A., Narayan, S., & Perez-Beltrachini, L. (2017, September). The WebNLG challenge: Generating text from RDF data. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Natural Language Generation (pp. 124-133).

-

Guo, Q., Jin, Z., Qiu, X., Zhang, W., Wipf, D., & Zhang, Z. (2020). CycleGT: Unsupervised Graph-to-Text and Text-to-Graph Generation via Cycle Training. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Natural Language Generation from the Semantic Web (WebNLG+) (pp. 77–88). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Ji, H., & Grishman, R. (2011, June). Knowledge base population: Successful approaches and challenges. In Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics: Human language technologies (pp. 1148-1158).

-

Leng, J., & Jiang, P. (2016). A deep learning approach for relationship extraction from interaction context in social manufacturing paradigm. Knowledge-Based Systems, 100, 188-199.

-

Liu, J., Chen, S., Wang, B., Zhang, J., Li, N., & Xu, T. (2020). Attention as Relation: Learning Supervised Multi-head Self-Attention for Relation Extraction. In IJCAI (pp. 3787-3793).

-

Raffel, C., Shazeer, N., Roberts, A., Lee, K., Narang, S., Matena, M., Zhou, Y., Li, W. & Liu, P. (2020). Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 21(140), 1-67.

-

Zhu, J. Y., Park, T., Isola, P., & Efros, A. A. (2017). Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (pp. 2223-2232).

@misc{thesis_domingo_2021,

title={Artificial Intelligence for Knowledge Generation and Knowledge Discovery},

author={Domingo, Oriol},

year={2021},

}