by Christine Basta

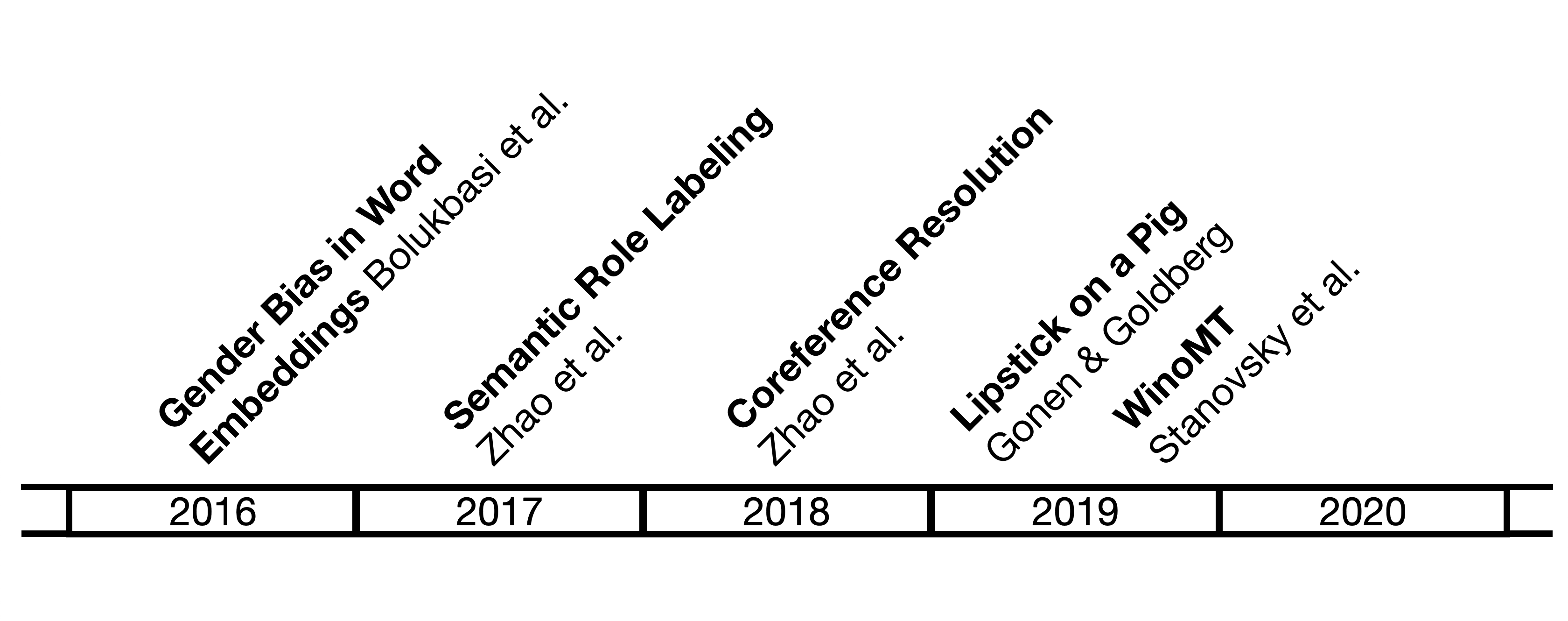

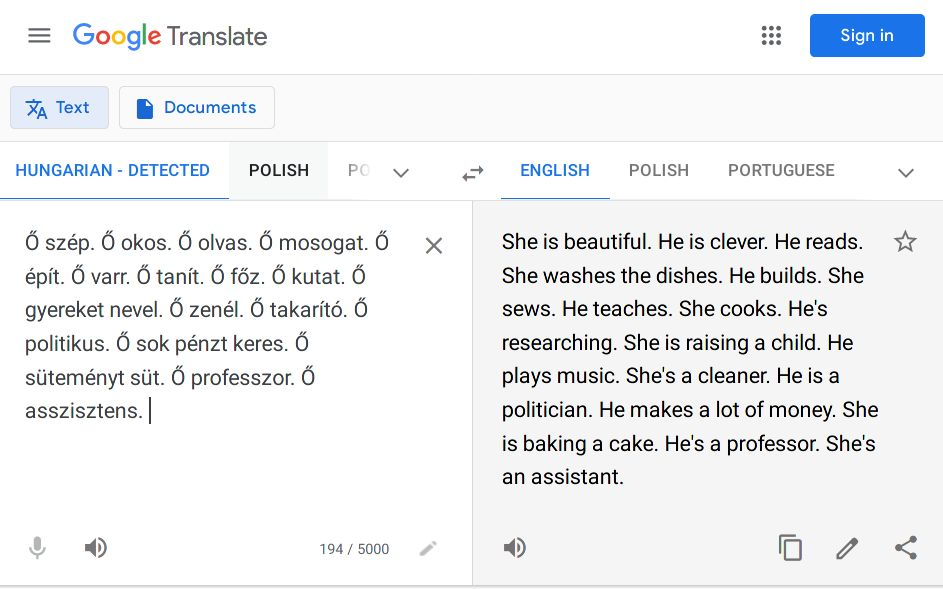

Recently, awareness of bias in Artificial intelligence (AI) has started to rise, thanks to researchers' and scientists' efforts. Natural Language Processing (NLP) can demonstrate an unpleasant level of biases, especially gender bias, as an actual AI application. Gender bias can be recognized when using different descriptions for women and men, dominating one over the other. Using terms such as 'working mother', 'female surgeon', and 'woman judge' are pre-modifying the occupation by gender specification, revealing the social stereotyping of such terms (Lu et al., 2020). While gender bias in NLP is mostly attributed to training on large amounts of biased data, the bias amplification is due to the learning algorithms, (Costa-jussà, 2019). Such bias impacts NLP applications, e.g., Machine Translation. An illustrative tweet was popular in the previous days revealing high gender bias when translating from Hungarian to English (Burkov, 2021). This article will discuss five papers that were considered important milestones in the journey of gender bias in NLP.

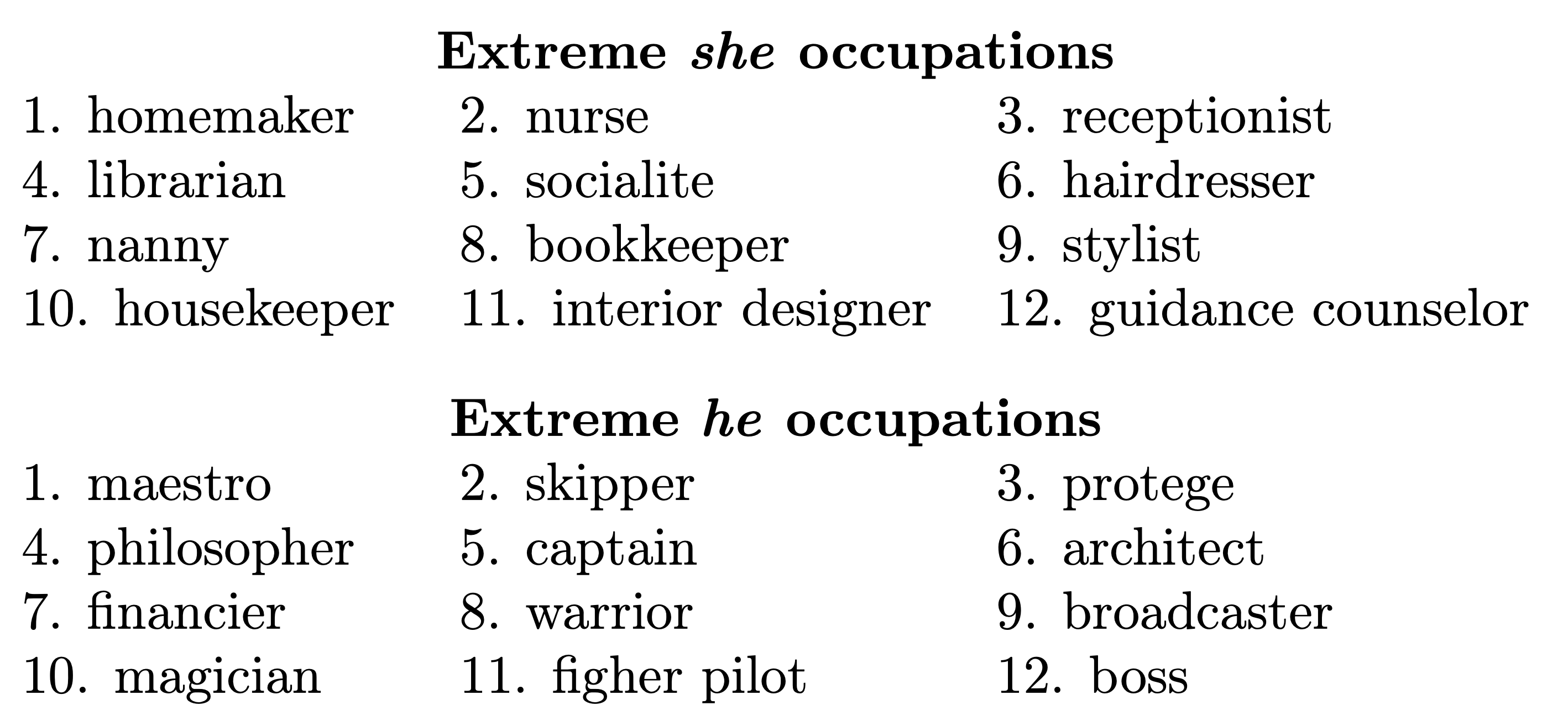

Bolukbasi et al. (2016) were the first to propose the problem of bias in embeddings to NLP communities, determine the concept of debiasing word embeddings, and establish the metric of measuring this bias (the gender direction). Gender bias of a word is defined to be its projection on the gender direction (difference between ‘he’ and ‘she’ vectors). The more the projection is, the more biased the word is. Their method showed the association between many words and social stereotypes, as shown in the figure below. Finally, they mitigate the bias by nullifying the information in the gender subspace for neural words and also equalizing their distance to both elements of gender-defining word pairs.

Even when we are trying to dissociate between neural words and gender, Gonen and Goldberg (2019) show that existing bias removal methods are insufficient. After debiasing embeddings, they clustered female and male-biased words in the vocabulary, according to the original bias definition of work from Bolukbasi et al. (2016). They also applied K-nearest neighbors on professions to see how words relate to gender and career. Moreover, they wanted to see if a classifier can learn to generalize from gendered or biased words to other words. Our paper adopted those techniques (Basta et al., 2021) to determine and evaluate gender bias in ELMo contextualized embeddings.

Added to these approaches, Caliksan et al., (2017) used gender-related association approaches to see relations between gendered words and different categories, e.g., family/career, art/mathematics, and art/science. All the experiments resulted that even after debiasing word embeddings, the debiasing is primarily superficial. There is a profound association between gendered words and stereotypes, which was not removed by the debiasing techniques.

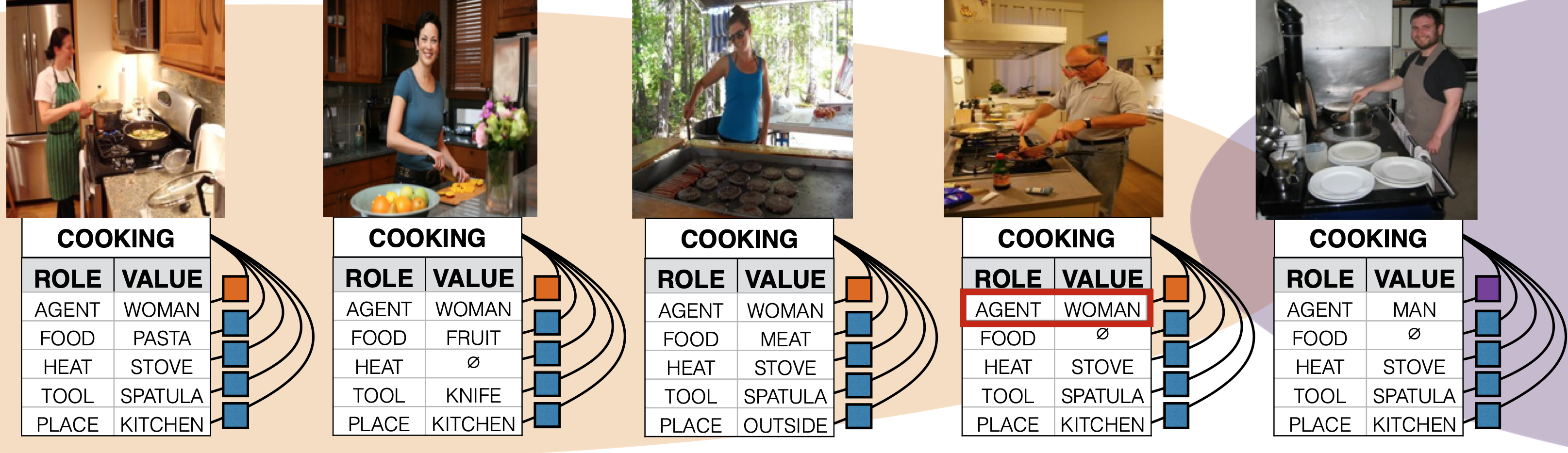

Another interesting approach (Zhao et al., 2017) relates NLP with visual analysis, where the authors studied the semantic role-labeling models and a famous dataset, imSitu. They realized that a higher portion of agent roles of cooking goes to women by 67% of the total. Additionally, they noticed that the model would amplify the bias and relate cooking images to men by only 16% after training. These observations show that models leverage social and gender bias.

A calibration approach called RBA (reducing bias amplification) was introduced in the paper. The approach depends on putting constraints on structured prediction to ensure that the model predictions follow the same distribution in the training data. They covered two cases in their study: multi-label object and visual semantic role labeling classification. The strategy showed an improvement in bias amplification in prediction. Five example images from the imSitu visual semantic role labeling dataset are shown in the figure. Each image is paired with a table describing a situation: the verb, cooking, its semantic roles, i.e., agent, and noun values filling that role, i.e.woman.

Two approaches to evaluating bias in coreference resolution were introduced by Zhao et al. (2018) and Rudinger et al. (2018). These approaches started by creating a new challenge corpus, WinoBias, and Winogender. Both follow the Winograd format (Levesque et al., 2011). It contains two types of challenge sentences in which entities have a coreference to either male or female stereotypical occupations, as shown in the figure below.

In the case of (Zhao et al., 2018), they trained the system on both original and gender-swapped corpora. To create the gender-swapped one, they constructed an additional training corpus where all male entities are swapped for female entities and vice-versa. Furthermore, to decrease the bias, they replaced GloVe embeddings with debiased vectors (Bolukbasi et al., 2016). They also balanced the male and female counts for noun phrases in gender lists to decrease the bias. They found that initially, the systems tend to amplify gender bias and relate professions to their stereotyped pronouns and their approaches affect the mitigation of gender biases in the system. The second approach (Rudinger et al., 2018) evaluated rule-based systems, feature-driven statistical systems, and neural systems on Winogender data. By multiple measures, the Winogender schemas reveal varying degrees of gender bias in all three systems. As expected, their main observation was that these systems do not behave in a gender-neutral fashion.

WinoMT (Stanovsky et al., 2019) is the first challenge test set for evaluating gender bias in MT systems. This test set is a combination of previous mentioned Winogender (Zhao et al., 2018) and WinoBias (Rudinger et al., 2018) sets, consisting of 3888 sentences of 1584 anti-stereotyped sentences, 1584 pro-stereotyped sentences, and 720 neutral sentences. Each sentence contains two personal entities, where one entity is a co-referent to a pronoun, and a golden gender is specified for this entity. An example of an anti-stereotypical sentence is demonstrated in the figure below, where ‘her’ refers to the ‘doctor’. The translation tended to stereotype the professions, giving the ‘doctor’ male gender and the ‘nurse’ the female gender. The evaluation mainly depends on comparing the translated entity with the specified gender of the golden entity to correctly gendered translation. Three metrics were used for assessment: accuracy (Acc.), and

. The accuracy is the correctly inflected entities compared to their original golden gender.

is the difference between the correctly inflected masculine and feminine entities.

is the difference between the inflected genders of the pro-stereotyped entities and the anti-stereotyped entities. The work of this paper has been utilized in these approaches for mitigating and evaluating gender bias in machine translation (Costa-jussà et al., 2020; Costa-jussà and Jorge, 2020; Basta et al., 2020; Saunders and Byrne, 2020; Saunders et al., 2020; Stafanovičs et al., 2020).

-

Basta, C., Costa-Jussà, M. R., & Fonollosa, J. A. R. (2020). Towards mitigating gender bias in a decoder-based neural machine translation model by adding contextual information. In Proceedings of The Fourth Widening Natural Language Processing Workshop (pp. 99-102). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Basta, C., Costa-jussa, M. R., & Casas, N. (2021). Extensive study on the underlying gender bias in contextualized word embeddings. Neural Computing and Applications, 33(8), 3371-3384.

-

Bolukbasi, T., Chang, K.W., Zou, J., Saligrama, V., & Kalai, A. (2016). Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates, Inc..

-

Burkov, A. [@burkov]. (2021, March 24). On biases in AI [Image attached]. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/burkov/status/1374534212188041218

-

Caliskan, A., Bryson, J., & Narayanan, A. (2017). Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science, 356(6334), 183–186.

-

Costa-jussà, M. R. (2019). An analysis of gender bias studies in natural language processing. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(11), 495-496.

-

Costa-jussà, M. R., Escolano, C., Basta, C., Ferrando, J., Batlle, R., & Kharitonova, K. (2020). Gender Bias in Multilingual Neural Machine Translation: The Architecture Matters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.13176.

-

Costa-jussà, M. R., & Jorge, A. (2020). Fine-tuning Neural Machine Translation on Gender-Balanced Datasets. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing (pp. 26–34). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Gonen, H., & Goldberg, Y. (2019). Lipstick on a Pig: Debiasing Methods Cover up Systematic Gender Biases in Word Embeddings But do not Remove Them. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (pp. 609–614). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Levesque, H., Davis, E., & Morgenstern, L. (2012). The winograd schema challenge. In Thirteenth International Conference on the Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning.

-

Lu, K., Mardziel, P., Wu, F., Amancharla, P., & Datta, A. (2020). Gender Bias in Neural Natural Language Processing. In Logic, Language, and Security (pp. 189–202). Springer International Publishing.

-

Rudinger, R., Naradowsky, J., Leonard, B., & Van Durme, B. (2018). Gender Bias in Coreference Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers) (pp. 8–14). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Saunders, D., & Byrne, B. (2020). Reducing Gender Bias in Neural Machine Translation as a Domain Adaptation Problem. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 7724–7736). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Saunders, D., Sallis, R., & Byrne, B. (2020). Neural Machine Translation Doesn't Translate Gender Coreference Right Unless You Make It. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing (pp. 35–43). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Stafanovičs, A., Pinnis, M., & Bergmanis, T. (2020). Mitigating Gender Bias in Machine Translation with Target Gender Annotations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Machine Translation (pp. 629–638). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Stanovsky, G., Smith, N., & Zettlemoyer, L. (2019). Evaluating Gender Bias in Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 1679–1684). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Zhao, J., Wang, T., Yatskar, M., Ordonez, V., & Chang, K.W. (2017). Men Also Like Shopping: Reducing Gender Bias Amplification using Corpus-level Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 2979–2989). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Zhao, J., Wang, T., Yatskar, M., Ordonez, V., & Chang, K.W. (2018). Gender Bias in Coreference Resolution: Evaluation and Debiasing Methods. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers) (pp. 15–20). Association for Computational Linguistics.

@misc{basta-major-breakthroughs-genderbias-nlp,

author = {Basta, Christine},

title = {Major Breakthroughs in... Gender Bias in NLP (VII)},

year = {2021},

howpublished = {\url{https://mt.cs.upc.edu/2021/03/29/major-breakthroughs-in-gender-bias-in-nlp-vii/}},

}