by Javier Ferrando

Translation systems are increasingly becoming more accurate. However, despite performance improvements, the understanding of their reasoning process has become less clear. This mainly occurs due to the fact that they are based on very deep neural architectures with hundreds of millions of parameters approximating complex functions. A better understanding of these deep learning models would allow researchers not only to further improve them but also make them more trustable since the model user and developer would know where the possible errors may come from. In this blog, we present the main works in the field of interpretability in NLP, with a focus on NMT.

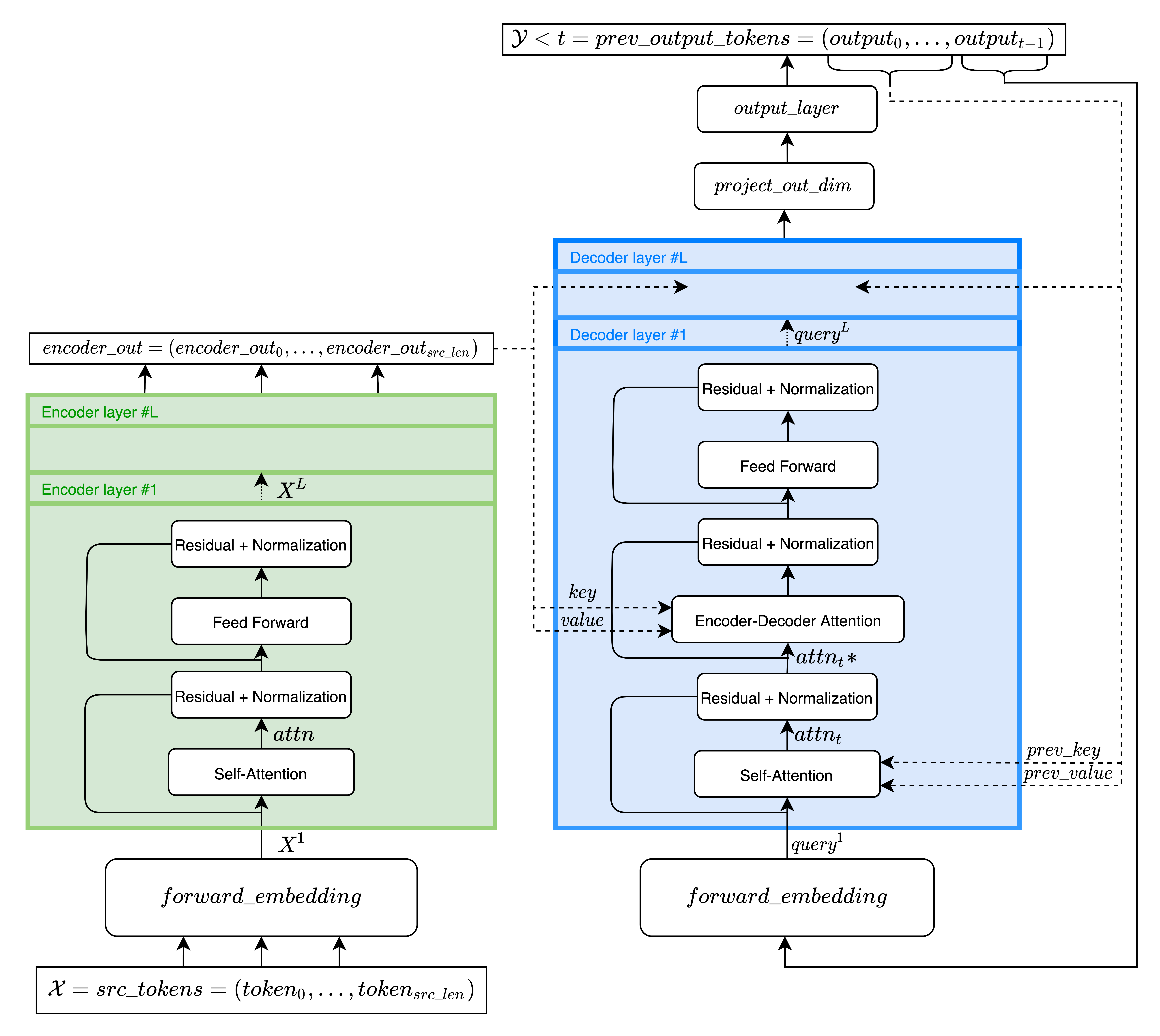

Jacovi and Goldberg (2020) propose two different criteria to define the interpretability of a model: plausibility and faithfulness. The former refers to how convincing to humans is the interpretation, while the latter refers to the level of accuracy at which the interpretation method depicts the reasoning behind the model’s prediction. Two main types of approaches have been explored in the NLP literature, post-hoc methods and building inherently interpretable models. Post-hoc methods' main advantage is that they are model agnostic since they try to explain the model prediction based on the relevance of the input tokens, this is also known as attribution. On the other hand, inherently interpretable models such as those with attention mechanisms have been developed, although their faithfulness has been criticized (Jain and Wallace, 2019; Serrano and Smith, 2019). Lately, the main used architecture in NLP has been the Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017), which is based on this attention mechanism and the efforts in the interpretability field have been mainly focused on this model.

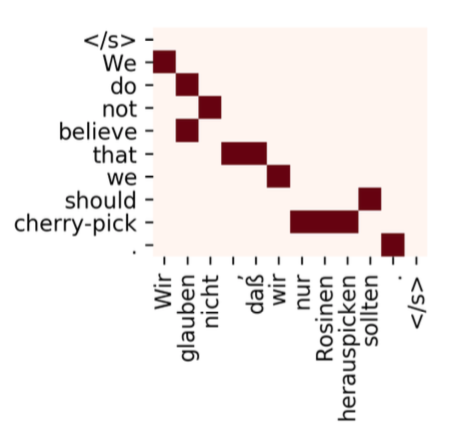

A common framework to evaluate interpretability methods regarding attribution is the word alignment task, which consists of finding many-to-many mappings between the source words to their translations in the target sentence.

Word alignment in NMT measures the importance of the input words when translating a target word. Therefore, it suits well the goal of attribution interpretability methods. A gold alignment dataset by human annotators is used to compare how well the interpretability method can extract word alignments from the model. Alignment Error Rate (AER) score is then used to measure how similar these alignments are with respect to the reference. SMT systems tend to perform better word alignments than neural approaches despite being less accurate in terms of translation performance. The reference system is GIZA++ (Och and Ney., 2003) which gets an AER of 21% in German-to-English translations.

Now we present the main interpretability methods that have been applied in the NMT literature. These methods include both post-hoc techniques and inherently interpretable models. As post-hoc methods, there are those based on the gradient and propagation-based ones. As for inherently interpretable models, there are those analyzing the attention mechanism.

Gradient-based methods are heavily used in this research field since they are easy to compute and can be used independently of the type of model. These methods are built on the assumption that the highly non-linear function of the neural network can be locally approximated by a linear model. By using the first-order Taylor expansion around a root point, the network can be approximated as:

measures the sensitivity of the output of the function with respect to the input vector x. The model sensitivity to a feature perturbation has been regarded as a possible measure for the "importance" of the feature. This method has firstly been applied in NLP (Li et al., 2016), which computes the mean of the components of the gradient w.r.t input token representation to get a sensitivity measure of each token.

A variation within the gradient-based methods is the gradient x input method (Denil et al., 2014). It basically consists of also computing the dot product between the gradient and the input vector. This gives a value of saliency of each word, which can be defined as the marginal effect of each input word on the prediction. (Ding et al., 2019) applied this method to get the word saliency in an NMT system. They contrast this method with the word alignment problem and obtain 36.4% AER in the German-to-English setting.

Several works (Jain and Wallace, 2019; Serrano and Smith, 2019; Clark et al., 2019) in the NLP field have tried to interpret models by studying the attention mechanism. The attention mechanism assigns weights to each of the input tokens, therefore seems to be logical to think that these weights are ideal to understand attribution. However, it has been found that this is not necessarily the case (Danish Pruthi et al., 2020). Kobayashi et al. (2020) go further on this topic and analyze the encoder-decoder attention module in a Transformer-based NMT system. Their main contribution is the use of not only the attention weights but also the norm of the vector by which the attention weights are multiplied. Using this method, they are able to achieve in German-to-English translations an AER of 25% in the second layer of the encoder-decoder attention module.

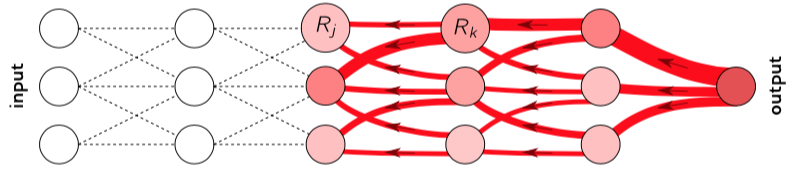

Layer-wise relevance propagation methods consist of computing a forward-pass through the network, where the predicted value for a certain class is obtained (Bach et al., 2015). This value is considered the total relevance of the network for that class. Then a backward-pass is done and for each layer, the relevance is distributed across the different neurons till the input is reached. Finally, a relevance score is given to each input element.

In NMT, Voita et al. (2020) use this method to measure the degree of contribution of the source sequence vs the target sequence when translating a certain word. NMT models translate sequentially. When translating the first word all the attention is given to the input sequence, but as tokens are produced by the decoder, they demonstrate that the attention is detoured towards the previously generated target tokens.

This research field is evolving fast, with a lot of new approaches appearing lately, both in the NLP and NMT fields. However, it doesn’t seem there is a clear direction into which methods get the clearest explanations, which shows that we are still in the early stages of the interpretation of deep learning models.

-

Bach, S., Binder, A., Montavon, G., Klauschen, F., Müller, K. R., & Samek, W. (2015). On pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. PloS one, 10(7), e0130140.

-

Clark, K., Khandelwal, U., Levy, O., & Manning, C. (2019). What Does BERT Look at? An Analysis of BERT's Attention. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACL Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP (pp. 276–286). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Danish Pruthi, Mansi Gupta, Bhuwan Dhingra, Graham Neubig, and Zachary C. Lipton. 2020. Learning to deceive with attention-based explanations. In Annual Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL).

-

Denil, M., Demiraj, A., and De Freitas, N. (2014) Extraction of salient sentences from labelled documents. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6815.

-

Ding, S., Xu, H., & Koehn, P. (2019). Saliency-driven Word Alignment Interpretation for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation (Volume 1: Research Papers) (pp. 1–12). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Franz Josef Och and Hermann Ney. 2003. A Systematic Comparison of Various Statistical Alignment Models. Computational Linguistics, 29(1):19–51.

-

Jacovi, A., & Goldberg, Y. (2020). Towards Faithfully Interpretable NLP Systems: How Should We Define and Evaluate Faithfulness?. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 4198–4205). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Jain, S., & Wallace, B. (2019). Attention is not Explanation. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (pp. 3543–3556). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Kobayashi, G., Kuribayashi, T., Yokoi, S., & Inui, K. (2020). Attention is Not Only a Weight: Analyzing Transformers with Vector Norms. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (pp. 7057–7075). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Li, J., Chen, X., Hovy, E., & Jurafsky, D. (2016). Visualizing and Understanding Neural Models in NLP. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (pp. 681–691). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Serrano, S., & Smith, N. (2019). Is Attention Interpretable?. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 2931–2951). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is All you Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates, Inc..

-

Voita, E., Sennrich, R., & Titov, I. (2020). Analyzing the Source and Target Contributions to Predictions in Neural Machine Translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.10907.

@misc{ferrando-major-breakthroughs-interpretability,

author = {Ferrando, Javier},

title = {Major Breakthroughs in... Interpretability in Neural Machine Translation (IV)},

year = {2021},

howpublished = {\url{https://mt.cs.upc.edu/2021/03/01/major-breakthroughs-in-interpretability-in-neural-machine-translation-iv/}},

}