by Noe Casas

The complete thesis on which this post is based can be found here. The individual articles can be accessed at: Linguistic vocabularies, Sparsely factored NMT, Word-subword Transformers, Iterative expansion language models.

Neural networks are said to be “black boxes”, as we cannot understand the behavior of the function learned by the network during training. This way, when the network generates an undesirable output, we cannot identify any reason why the output is different from the desirable one. This makes neural networks difficult or impossible to fix in a traditional way a software bug is fixed. This also implies that translations generated by NMT systems are not interpretable, in the sense that we cannot establish a causal relationship between the parts of the input sentence, specific parts of the computation, and the generated output.

Apart from the inherent lack of interpretability in neural nets, the ubiquitous vocabulary definition strategies used currently in NMT systems (byte-pair encoding and unigram tokenization) consist of finding subword segments that are statistically highly reusable in the training data. These subwords, nevertheless, have no morphological grounding and may be totally unrelated to the morphological segmentation that a linguist may apply to words, preventing most attempts at a morphological interpretation of the internal model dynamics. Also, in NMT, the input and output texts are handled as a mere sequence of tokens, disregarding any explicit syntactic structure of the data.

The fact that the information handled by the neural network is totally unrelated to morphology, syntax, or any other linguistic framework, together with the black-box nature of neural networks, makes NMT translations unexplainable, even more, if compared with the formerly dominant rule-based machine translation paradigm, which relied completely on linguistic information and was fully interpretable.

There have been many lines of research that proposed injecting different types of linguistic knowledge in NMT systems, mainly aiming at improving the translation quality. Such improvements of translation quality via linguistic knowledge are certainly possible, especially in low-resource scenarios, morphologically rich languages, and out-of-domain inference texts. However, in scenarios with abundant training data and in-domain inference texts, the improvements obtained with linguistic knowledge are almost negligible.

Nevertheless, linguistic knowledge can still play an important role in NMT systems: to serve as a bridge between the black box effective neural systems and our linguistic conception of languages. Here, we have a glance at four proposals in that direction. Please do not hesitate to read the full articles for the detailed discussions and results of each proposed approach.

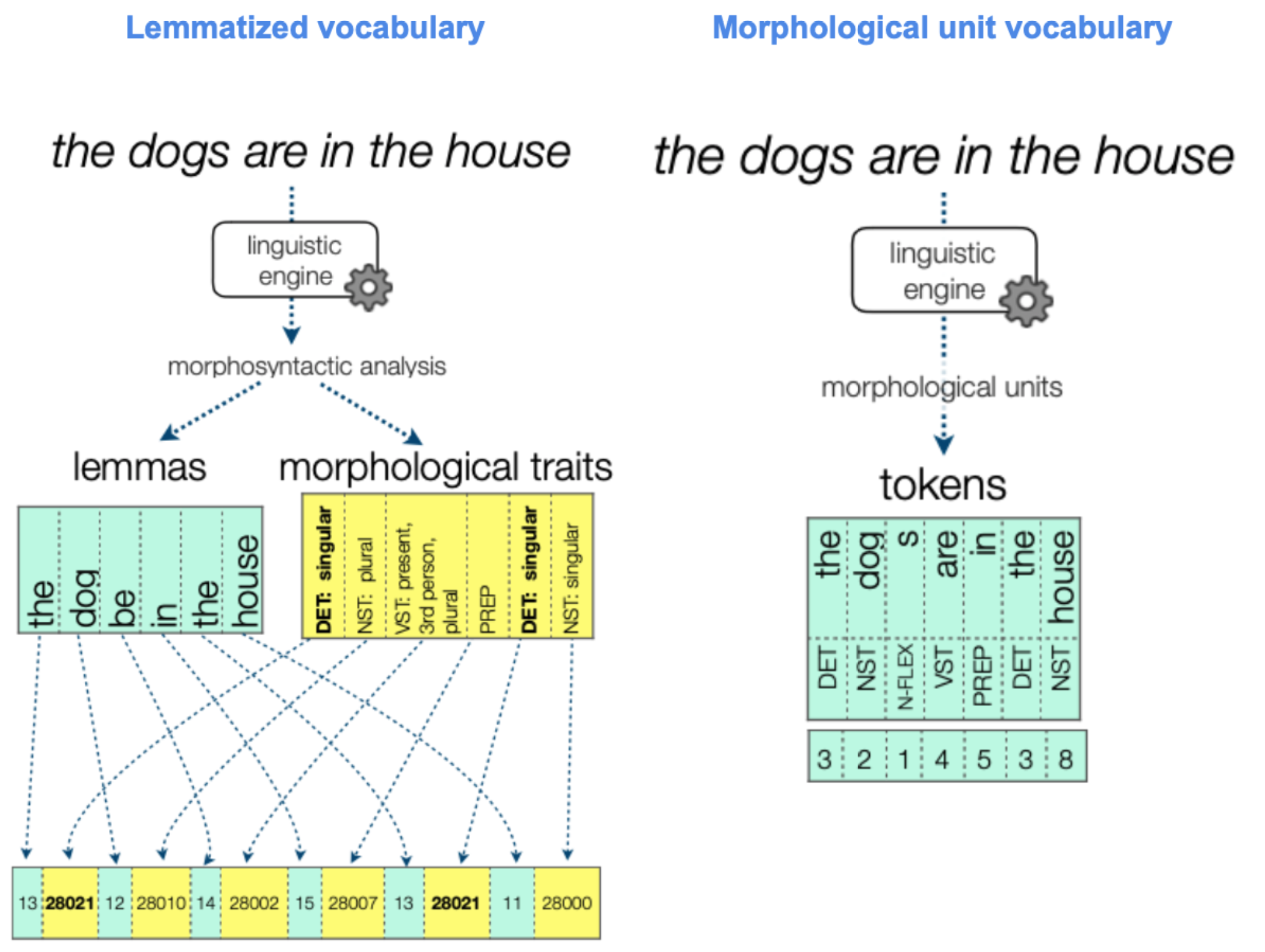

Our first proposal in that line is presented in (Casas et al, 2021), where we define two novel ways of using purely linguistic vocabularies in a standard Transformer network. The first of our linguistic vocabulary definition strategies (“lemmatized vocabulary”) consists in having each word represented by two tokens: the first one is a “lemma token”, representing the lemma of the word, while the second token represents the morphological traits of the word (e.g. number, gender and case for German nouns). The second linguistic vocabulary strategy (“morphological unit vocabulary”) relies on a morphological subword segmentation, where each subword has associated morphological traits (e.g. the subword “s” being a number flexion for nouns in English). The use of linguistic tokens allows us to characterize the translations in terms of the linguistic input phenomena, while not losing the flexibility and desirable traits of statistic subword vocabularies.

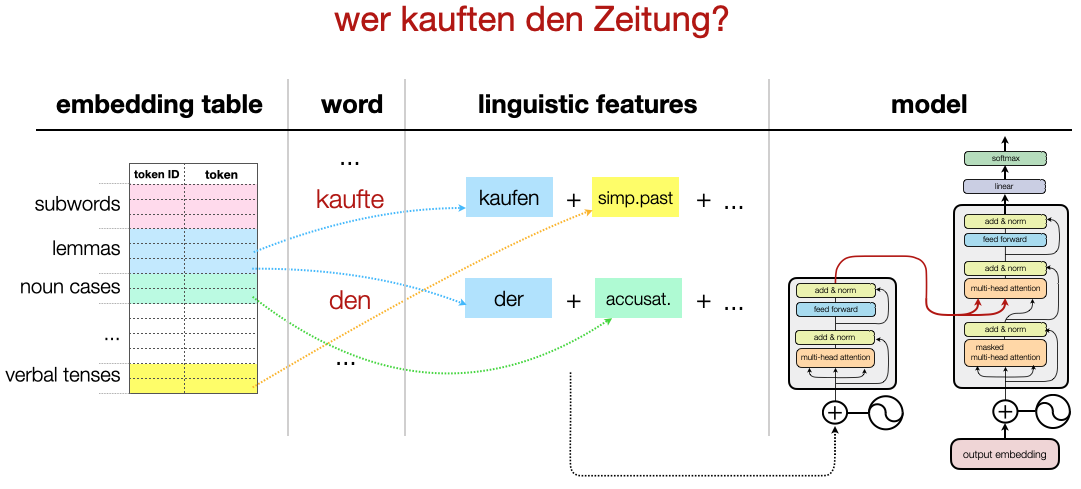

Our second proposal, from (Casas et al, 2021), is called Sparsely factored NMT, and consists of an evolution of the previously described linguistic vocabularies. The problem we try to solve here is sparsity in the linguistic information normally suffered in the traditional Factored NMT approaches: when we represent a combination of morphological traits as a single token, it may not appear frequently in our training data, leading to poor training signal. Instead of using a different token for each combination of morphological traits, we decouple each different trait value (e.g. plural number, singular number, simple past tense, nominative case, etc) and, for each value, we have a different embedded vector. In order to represent a word, we add together the embedded vector of its lemma together with the vectors of each of the morphological traits of the specific surface form of the word. This reduces notably the sparsity of the training signal, as the individual values appear much frequently than each different combination of them.

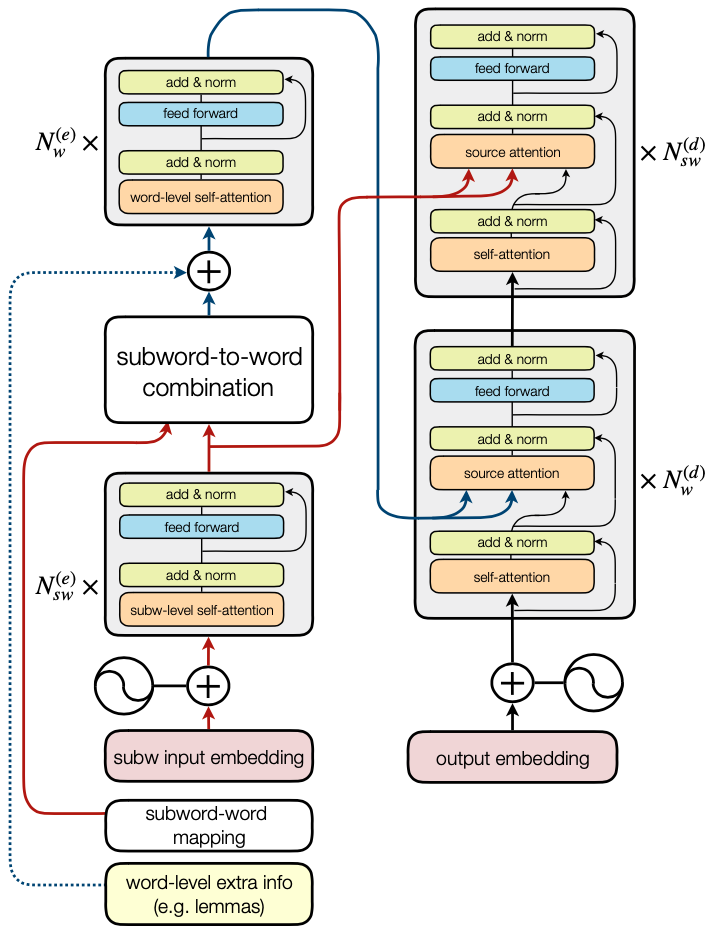

Our third proposal, from (Casas et al., 2020), steps into the architectural aspects of the NMT model to incorporate linguistic information. The problem this proposal aims at addressing is the mismatch between two situations: first, to obtain SoTA translation quality you need subword vocabularies; second, the linguistic information is defined at word level (e.g. lemma, gender, verbal tense), not at subword level. Other approaches like Factored NMT “copy” the word-level linguistic information to each of the subwords in the same word. Here, we propose to modify the architecture of the Transformer model to provide a suitable point to inject word-level information. For that, we introduce a layer that combines subword representations into word-level representations, making use of the subword-to-word associations. This, however, makes it difficult to profit from the strengths of subword NMT systems in terms of being able to copy unseen words from source to target; to mitigate this problem, we only maintain word-level representations in the middle layers of the Transformer, keeping the subword representations in the first and the last ones. This approach allows maintaining the translation quality while providing a natural point to inject word-level linguistic information into our models without any subword mismatch.

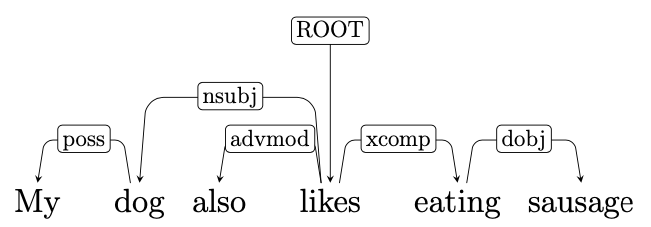

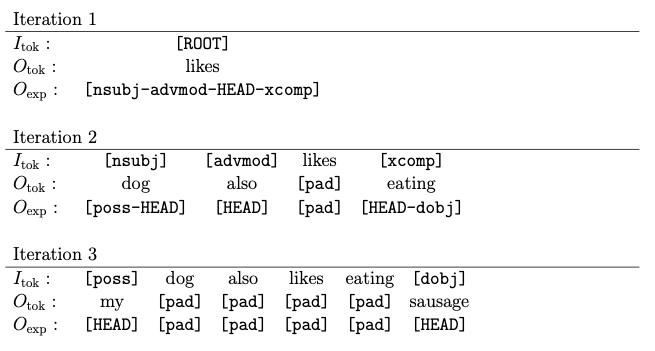

Our final proposal, from (Casas et al., 2020), aims at driving the text generation process with the syntactic structure of the sentence. For this, we train a Transformer model to generate iteratively the sentence dependency tree up to the terminal leaves representing words and subwords. At each decoding iteration, the model receives as input a sequence that can contain both terminal tokens (i.e. words or subwords) or “dependency tokens”, which represent branches of the sentence dependency tree still to generate, while as output it generates non-autoregressively two sequences of the same length as the input. The first output represents terminal tokens associated with the placeholders in the input; the second output contains “expansion placeholders”, which represent how the further branches of the tree should be expanded (e.g. the expansion placeholder [HEAD-dobj] represents that the word at that position (HEAD) has a direct object dependency to its right (dobj)). This iterative generation scheme allows for sentences to be generated according to their syntactic dependency structure, making it also possible to control the resulting style of the generation process by favoring some syntactic constructions; we illustrate this by making the generated text more descriptive by artificially increasing the probability of generating adjectival construction.

The articles described in this post were joint work with my PhD advisors, Marta R. Costa-jussà and Jose A. R. Fonollosa, together with colleagues from Lucy Software (the company that hosted this research), Juan Alonso and Ramón Fanlo. I would like to thank my advisors and Lucy Software for this opportunity, and the Catalan Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR), which funded the Industrial PhD Grant that made it possible.

@article{casas_costa-jussa_fonollosa_alonso_fanlo_2021,

title={Linguistic knowledge-based vocabularies for Neural Machine Translation},

volume={27},

DOI={10.1017/S1351324920000364},

number={4}, journal={Natural Language Engineering},

publisher={Cambridge University Press},

author={Casas, Noe and Costa-jussà, Marta R. and Fonollosa, José A. R. and Alonso, Juan A. and Fanlo, Ramón},

year={2021},

pages={485–506}

}

@article{casas2021sparsely,

title={Sparsely Factored Neural Machine Translation},

author={Casas, Noe and Fonollosa, Jose AR and Costa-jussà, Marta R},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.08934},

year={2021}

}

@inproceedings{casas-etal-2020-combining,

title={Combining Subword Representations into Word-level Representations in the Transformer Architecture},

author={Casas, Noe and Costa-jussà, Marta R. and Fonollosa, José A. R.},

booktitle={Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Student Research Workshop},

year={2020},

publisher={Association for Computational Linguistics},

url={https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-srw.10},

doi={10.18653/v1/2020.acl-srw.10},

pages={66--71},

}

@inproceedings{casas-etal-2020-syntax,

title={Syntax-driven Iterative Expansion Language Models for Controllable Text Generation},

author={Casas, Noe and Fonollosa, José A. R. and Costa-jussà, Marta R.},

booktitle={Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Structured Prediction for NLP},

month={nov},

year={2020},

address={Online},

publisher={Association for Computational Linguistics},

url={https://aclanthology.org/2020.spnlp-1.1},

doi={10.18653/v1/2020.spnlp-1.1},

pages={1--10},

}