by Marta R. Costa-jussà, Gerard I. Gállego, Javier Ferrando & Carlos Escolano

The motivation of this blog is to share our research findings in a more understandable format than standard academic papers. Today, we are pleased to present a post series where we will describe the background of the main topics we are working on, with a guided tour through the most influential papers. With this contribution, we want to reach a non-expert audience, whether merely interested in our lines of research or potential students of our group.

In the first post, we will start from scratch on the fascinating topic of Neural Machine Translation.

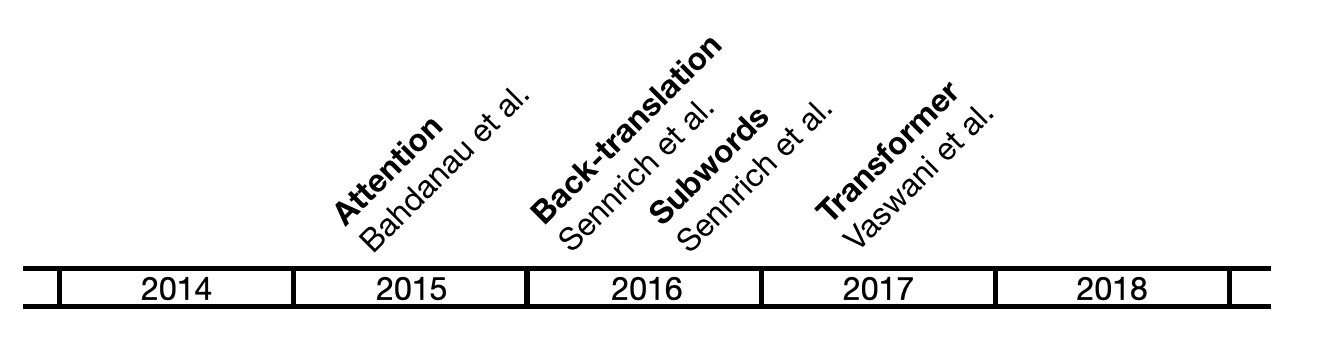

Back in 2014, the rise of deep learning had already surprised the community in areas such as image processing (Krizhevsky et al., 2012). However, MT translation was still a challenge for neural approaches because it had to deal with variable length sequences in the input and the output. Sutskever et al. (2014) solved this problem by proposing an encoder-decoder architecture, which led the community to consider neural machine translation (NMT) a serious alternative to statistical machine translation systems, rather than a simple feature of it (Schwenk et al., 2006). While statistical models were trained on two separate steps (alignment and translation modelling), the neural approach proposed to train and model the conditional probability of producing a target sequence, given the source sequence, in an end-to-end fashion. The encoder computes a representation of the input sequence, and the decoder generates a sequence based on the encoder representation. Within this first approach, collapsing the entire source sentence into a single vector representation was a strong bottleneck that did not allow the NMT model to outperform the statistical systems. Bahdanau et al. (2015) overcame this limitation by introducing the attention mechanism, which supposed the beginning of the NMT paradigm. It was followed by big successes such as subwords (Sennrich et al., 2016a), back-translation (Sennrich et al. 2016b), and Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017).

The first breakthrough that allowed NMT to obtain state-of-the-art results was attention, which solved the issues caused by the bottleneck between the encoder and the decoder (Bahdanau et al., 2015). It addressed the problems of token repetition and partial translation that previous architectures showed due to representing the whole sentence in a single vector, thus creating an information bottleneck. The attention mechanism allows the network to adjust the encoder representation for each decoding step by weighting the amount of information provided by each source token. When the decoder needs to generate a word, it computes the attention score between every input representation from the encoder and the current decoder state. Then, the decoder uses these scores to calculate the weighted sum of the input representations, which is used to generate the next token. Apart from Bahdanau’s, several methods have been proposed as score functions (Luong et al., 2015).

When using neural approaches for modelling language, either conditioned or unconditioned, the vocabulary size has been an issue for a long time (Bengio et al., 2003). The last layer of these architectures consists of a softmax that computes the probability of each word over the entire vocabulary. The only way to efficiently face it has been limiting the vocabulary size. This limitation had the consequence of having plenty of out-of-vocabulary words. One alternative to this was to use character-based models (Costa-jussà & Fonollosa, 2016), since the vocabulary of characters is already limited compared to the words’. More than this, Sennrich et al. (2016a) proposed to use byte pair encoding to break the words into subwords, having the best of both worlds: words and characters. Subwords are created from the most frequent sequences of characters up to a certain number of merges that is defined. Therefore, most probable combinations appear together, while the less frequent are represented as individual characters. With this approach, the problem of unknown words is solved, while keeping an acceptable vocabulary size. The advantage of subwords over characters is clear in terms of performance and efficiency, because using characters requires much longer sequences that slowed the training process. Furthermore, in terms of translation quality, subwords represent semantic information better than characters, which can be crucial for the model performance.

Beyond the previous vocabulary and attention challenges, the scarcity or lack of parallel corpora was a relevant problem for the neural approach. In low resourced environments, statistical systems were still better suited (Koehn & Knowles, 2017). One reason was that statistical systems could take advantage of large monolingual language models, while the integration of this idea was not very clear in neural approaches (Gulcehre et al., 2017). This limitation was solved with the idea of back-translation (Sennrich et al., 2016b). In back-translation, we automatically translate a monolingual corpus to generate a parallel pseudo-corpus, where the source language is synthetic and the target language is not. Experiments show that this technique highly improves the translation quality, being an efficient option to exploit the large quantities of monolingual available.

With the advent of harnessing large amounts of data into the system by using techniques like back-translation, it became more visible that using recurrent neural networks for training was a limitation. Basically, with these types of architecture, the training process can not be parallelized and it has to be sequential, since in a recurrent neural network each step depends on the previous one. More than this, RNNs have the practical issue that they do not perform well in very long sequences (>200). The use of convolution neural networks (Gehring et al., 2017) allowed for parallel training, at the cost of higher memory consumption. Finally, the Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) relied only on attention layers combined with fully-connected ones, allowing parallelization and showing remarkable performance in long sequences. The impact of this architecture exceeds the limits of NMT (Vinyals et al., 2019) and we are proud of having devoted the first post of our blog to it, where we explained the Transformer architecture, focusing on the Fairseq implementation, and describing its essential modules and operations.

While NMT has not even come close to solving all the challenges that machine translation has, it raises new opportunities towards universal communication. In the following posts, we are discussing the background and progress in the subareas of multilinguality, speech translation, bias, interpretability, linguistics, lifelong learning and unsupervised learning.

-

Bahdanau, D., and Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2015). Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, Conference Track Proceedings.

-

Bengio, Y., Ducharme, R., Vincent, P., & Janvin, C. (2003). A neural probabilistic language model. The journal of machine learning research, 3, 1137-1155.

-

Costa-jussà, M. R., & Fonollosa, J. A. R. (2016). Character-based Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (pp. 357-361).

-

Gehring, J., Auli, M., Grangier, D., Yarats, D., & Dauphin, Y. N. (2017). Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 1243-1252). PMLR.

-

Gulcehre, C., Firat, O., Xu, K., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2017). On integrating a language model into neural machine translation. Computer Speech & Language, 45, 137 - 148.

-

Koehn, P., & Knowles, R. (2017). Six Challenges for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Neural Machine Translation (pp. 28–39). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 25, 1097-1105.

-

Luong, T., Pham, H., & Manning, C. (2015). Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 1412–1421). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Schwenk, H., Costa-jussà, M. R., & Fonollosa, J. A. R. (2006). Continuous space language models for the IWSLT 2006 task. In IWSLT-2006, 166-173.

-

Sennrich, R., Haddow, B., & Birch, A. (2016a). Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 1715-1725). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Sennrich, R., Haddow, B., & Birch, A. (2016b). Improving Neural Machine Translation Models with Monolingual Data. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 86–96). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O., & Le, Q. (2014). Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2 (pp. 3104–3112). MIT Press.

-

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is All you Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 5998–6008).

-

Vinyals, O., Babuschkin, I., Czarnecki, W.M. et al. (2019) Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 575, 350–354.

@misc{costajussa-major-breakthroughs-nmt,

author = {Costa Jussà, Marta R. and Gállego, Gerard I. and Ferrando, Javier and Escolano, Carlos},

title = {Major Breakthroughs in... Neural Machine Translation (I)},

year = {2021},

howpublished = {\url{https://mt.cs.upc.edu/2021/02/01/major-breakthroughs-in-neural-machine-translation-i/}},

}